History

Debrecen’s first public cemetery built for the civilian population of the town opened in 1932. The burial spaces for families and individuals established among the artistically designed forest walkways did not at the time include separate plots for burying people of different religious denominations. The offspring of deceased loved ones who were reinterred from the Calvinist and Catholic cemeteries, closed at the same time as the new cemetery’s opening, did not have them buried in separate rows of graves. The strict regulation governing this was overwritten during World War II, when the town was drawn into the military conflict. After the older military cemeteries were full, parts of the new public cemetery were separately allocated for the large number of fallen soldiers. The town of Debrecen, which was responsible for maintaining the Public Cemetery, designated special plots, e.g. on 2 June 1944 for the victims of air raids and a graveyard for fallen heroic Hungarians. The victorious Soviet army utilised a separated part of the cemetery for its dead on its own initiative.

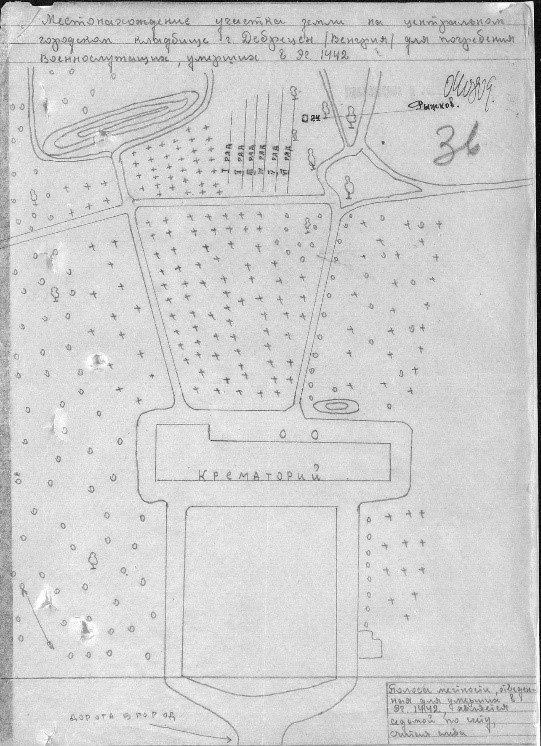

The mortuary in the public cemetery

Apart from the exclusively military graveyards of Debrecen’s Public Cemetery, there are numerous military graves to be found among the various other plots. (1) Although the cemetery opened in 1932, we encountered a good many names of national guard and army officers who fought in 1848/49 and who after the failure of the struggle for freedom returned to their civilian professions; these include musicians, pharmacists, doctors, mayors and preachers. One can also read the names of fallen heroes from the first and second world wars on the graves, who do not necessarily lie there as in some cases their families only erected a memorial stone to them. One can also find names of former soldiers who were born in the city or who stayed in Debrecen after retiring, as well as the names of regimental commanders from World War I and Debrecen garrison commanders who were once known and esteemed individuals in the town. Their graves were removed to the public cemetery after the denominational cemeteries were closed. (2) Perhaps the most interesting among them is the k.u.k. Hussar captain and later Hungarian royal bodyguard officer, who fought in the Italian campaign of 1866. His name had once been well known throughout the Monarchy. The ‘Sebetic-fencing system’ was named after him, while an instruction manual on sword fencing, published three times, and a rule book on duels, published four times, are also linked to his name.

There are fallen soldiers in the cemetery from the interwar period. For example, a former soldier of the k.u.k. 39th infantry regiment lies here, who in 1900 was reallocated to the Hungarian royal 3rd infantry honvéd regiment (regiment of the Hungarian army in the revolutionary war of 1848-49) and finally retired as the commander of the 23rd Nagyszeben infantry regiment. One can also find heroes from World War I who returned home from the Great War and passed away after the cemetery was opened. The commander of the 2nd Hussar home defenders also lies here, as well as the commander of the 3rd territorial infantry regiment and the commander of the 39th infantry regiment, which was Debrecen’s local infantry regiment. It is also the cemetery and final resting site for soldiers of the former 39th infantry and for the 3rd home defender and 2nd Hussar regiments of the Hungarian army. Some of them were buried in honorary graves, while the graves of others – who did not have relatives at the time of their burial – were either forgotten, or terminated according to the regulations of the cemetery.

Graves of soldiers from World War II in Debrecen’s Public Cemetery

As a continuation of a digital publication on Debrecen’s Heroes’ Cemetery and Military Cemetery as well as its former and existing denominational cemeteries, research was launched into the military graves of the Public Cemetery opened at the time when the denominational cemeteries were closed.2 Unfortunately, this research project could only be carried out with more modest sources of information than the previous one since the military graves given a place here for soldiers of World War II were viewed very differently after 1945 to the military cemeteries and military graves established during the Great War. In the decades after WWII out of the military graves holding the bodies of four nations, every effort was made to forget about the graves of two: the Hungarians and Germans. However, it is worthy of note that even during the decades of the party state these unwanted graves were not terminated. In contrast, the graves of the victors were tended to and they remained well-looked-after but, as will be shown later, the locally available sources provide the least information on the latter.

According to initial plans, the main objective of the research would have been to focus on section XXII, containing the resting places of the Hungarian prisoners-of-war established in 1945, section XV/3, containing the graves of the victims of air raids (the so-called ‘plot of the bombed’), section IX, which is a mass grave of Romanian soldiers, and section XVI/A, i.e. the Soviet graveyard. As the research progressed, it transpired that the graves in the public cemetery established in 1932 covered a broader time frame than previously assumed. It was surprising that the units stationed in different barracks in Debrecen suffered losses in personnel from the most diverse of reasons, which did not include being sent to the front. The soldiers who died from illnesses, accidents or suicide were not buried in the Military Cemetery (there were no burials there during World War II until 1943) but instead in various sections of the Public Cemetery. Knowing this, the research was extended to graves of civilians who died during the battle to occupy Debrecen and in air raids. The reason for this was because it was already necessary to consider the entire area of the Public Cemetery in relation to the military graves and it was, therefore, expedient to make a list of the civilians who had died as a result of the fighting. In tandem with this, the time interval covered by the research was defined as the period from when Hungary entered the war (27 June 1941) all the way until early 1946. It also became obvious that the soldiers reinterred in the Public Cemetery by their relatives after WWII would not become the focus of the research. In many cases it transpired that the names on the graves that were erected did not necessarily mean that the heroic dead brought home were actually lying there, but merely that the relatives wished to put up a monument in this form to their heroes buried in a far-off field; this line of research was thus impossible to follow.

The primary sources of the data processing were the Public Cemetery’s funeral inventory books, section books and indices of names. The books provided the burial places of Hungarian and German soldiers as well as civilian victims with great accuracy, and what may have happened later to the graves (exhumation, termination, reinterment etc.). The situation is not so clear in the case of Soviet and Romanian soldiers. The Soviet Red Army and the Romanian units attached to it buried their heroic dead in temporary graves on the edges of the city or in various locations in the central parts of Debrecen. They also carried out the administration for the graves themselves. No data whatsoever can be found in the Hungarian inventories relating to when these remains were removed to the Public Cemetery. In conformity with their typically suspicious approach and propensity to keep secrets, the Soviets provided no data.

The various searchable online databases proved to be very helpful. They helped to clarify the data for the German soldiers, while surprisingly large amount of data emerged on the Soviet soldiers along with contemporary, accurately-listed records of losses as well as contemporary sketches of the grave sites. The material found in Hajdú-Bihar County Archives of the Hungarian National Archives proved to be an invaluable source of information: it provided data about soldiers exhumed in various points of the city.

The graves of Hungarian soldiers

The connection between the Military Cemetery and the Public Cemetery is very interesting in respect to the military graves. When the Military Cemetery was closed in 1945, the official reason for non-expansion was that the Public Cemetery had already lost its civilian character after Soviet soldiers and soldiers who had died in air raids and because of other reasons were buried there. In contrast with this, military graves had been placed in the Public Cemetery years before the Military Cemetery was reopened in 1943.

The first to be buried were Hungarian soldiers. Following Hungary’s entering the war in 1941, as mentioned in the introduction, twelve soldiers died by the end of the year from illness, suicide or accidents. Their units are not known but in two cases their barracks reveal that they were from Debrecen units, while in the other cases the Debrecen garrison hospital registered their place of death. During the whole of 1942, the number of soldiers dying while on active service had already risen to 48. During these two years – unless their relatives had them transported out of Debrecen – the majority of them were buried in section XIV/B. In all probability they would have been exhumed from since today only one military grave can be found here. Soldiers were buried in section XVI from the end of 1942. The majority of the 62 soldiers who died in 1943 were buried in section XVI. The situation of the graveyard was somewhat similar to section XIV; only a few military graves can be found there, which had not been terminated only because of the relatives who had died later and been buried there. As a result of this, the military characteristics on these graves is not evident. There are two isolated and sunken slant markers (pillow stones) in the first row of the section for the graves of honvéd soldiers Mátyás Hovorka and György Ráduly. The dramatic events of 1944 began with the allied air raids. The victims and heroic dead of this destruction were buried in the first half of section XV/3, now known as the ‘plot of the bombed’, while some Hungarian soldiers who died in an air raid in September were laid to rest in the back part of this section. Of course the opportunity afforded itself here too for relatives to bury their dead in family graves or to have them removed from Debrecen. In accordance with the general regulations on burials, the period of internment had to be taken into account: after its expiry, if the place of the grave was not paid for, any grave could be terminated. Because of some tacit agreement to protect this section, no graves were terminated in section XV/3 even during the tenure of the party state but remains could be exhumed from here and buried elsewhere upon the request of the families of those interned here.

„Bombázottak” sírkertje a Köztemetőben

Before 19 October 1944, most of the burials of the heroic Hungarian soldiers killed in the fighting that took place in October of that year were carried out by Hungarian soldiers themselves. These heroes were also placed in the first row and the separate rows of section XV/3. Personal data on the Hungarian soldiers temporarily buried in Debrecen’s outlying and inner areas after the fall of the town rarely came to light; some of them were ascribed a final resting place as unknown soldiers in the last rows of XV/3, and others, when necessity required, were buried in one of the now non-existent plots XIX/1, XIX/2 and XIX/3, which at the time were used for free burials.

At present, we have the data of 36 Hungarian soldiers whose Debrecen graves are not known, while the words “remains unburied” can be read on the cards on losses (3) issued about a further eight Hungarian soldiers. In all probability, they were added to the number of the unknown heroic dead later exhumed. Upon examining the distribution of the soldiers according to units, it can be ascertained that during the fighting in Debrecen it was the 16th artillery assault division that suffered the gravest loss among the Hungarian units. Twenty-seven soldiers of this unit were buried in section XV/3. The second greatest loss – eight soldiers – was suffered by those sections of the 2nd armoured division that were relocated to Debrecen. Presumably, the heroes of the combat unit who formed the 12th reserve division also rest here, although there is no solid data to prove this. We know of another 16 Hungarian soldiers who were also victims of the fighting in October but they were not buried in the two burial places mentioned above but in section XXII. It can be said about three of them with certainty that they died of their wounds in the clinic and were first buried on its premises. (4) It was from here that they were probably exhumed with other soldiers and civilians between 10 and 12 October and then buried in the Public Cemetery. Relatively late after the war (in 1948-49), five more unknown soldiers were exhumed from other areas of Debrecen and reinterned in section XXII.

THE SECTION FOR HUNGARIAN HEROES IN DEBRECEN’S PUBLIC CEMETERY

On the map of today’s Public Cemetery, one part of section XXII bears the name “Hungarian heroes”. Apart from those mentioned above, this section also serves as the final resting place for the prisoners-of-war who came to Debrecen between 1945 and 1949 and died of illness or exhaustion. The “Pavilion” garrison was designated as a screening station for the prisoners-of-war that returned home from the Soviet Union. The men dying of exhaustion were cared for as best conditions allowed at the Red Cross military hospital number 101 set up here. (5) Sick prisoners-of war were also taken to the first aid post set up in the former Jewish secondary school building at 6 Hatvan Street, as well as to the Augusta sanatorium and the clinic. Between 4 January 1945 and 9 January 1949, 322 men died in the hospitals and first aid posts from their terrible injuries. There are 62 Hungarian prisoners-of-war in the mass grave for Soviet soldiers in section XVI/A. (6) The situation, which is rather controversial (former enemy soldiers buried among the rows of Soviet graves), was presumably caused by the Soviets themselves, although the lack of data means the explanation will be forever shrouded in mystery.

There are now few remaining Hungarian military graves in section XV/3 because in 1997 the German League for War Graves reached an agreement with the leaders of Debrecen and the administrators of the Public Cemetery at the time to exhume (7) the remains in neglected military graves and to rebury them in the German-Hungarian military cemetery (Békepark, which means Park of Peace), established in Budaörs at the time.

The graves of German soldiers

The secret as to how the graves of German soldiers survived until 1997 is explained by the majority of them being in section XV/3. This was the burial place for the Germans who died in the air raids on Debrecen and in the fighting prior to the fall of the town. They were laid to rest by their comrades, and often in quite strange circumstances. For example, the note “arbitrary burial by the Kassai gate” can be read in the cemetery’s burial inventory book under Lieutenant Horst Möbis and Oberfähnrich Heinz Ortlepp. (8)

During the fighting to take Debrecen on 19-20 October 1944, it was not unusual for the dead bodies of both Hungarian and German soldiers to be strewn all over the city unburied. They were typically buried in temporary graves in the closest possible places (the most practical being the places where the bodies were discovered). These soldiers were entered in the inventory book as unknown and after being exhumed their remains were placed in unmarked graves between rows 2 and 3 as well as between rows 3 and 4 and at the beginning of row 1 of section XV/3. Some of them were buried haphazardly in several points of section XV/3. In 1945, 28 German prisoners-of-war were placed in the separate row of graves and in row 1 of section XV/3. Their inclusion filled almost the whole section and thereafter there were no more burials. Only three of the graves for German soldiers in the section of the bombed had gravestones; these were erected by their families (in two cases the addresses of the families are known). Two of the soldiers laid to rest there lost their lives in an air raid. The third grave (grave 27 in the second row of the section) contains the remains of four German soldiers, who died at the dressing station of the German ambulance company 128/1 operating in the Svetits Institute and were first buried in its courtyard (three with names and one unknown). During the exhumation in 1997, mentioned above, it was not important if a particular grave of a German soldier had been tended to since the remains of all of them were transported to the Budaörs military cemetery. The gravestone on what was once the resting place of the four German soldiers has survived to this day, serving as a quasi-monument to the German soldiers once laid to rest there.

Section XXII marked “Hungarian heroes” in Debrecen’s Public Cemetery also contains German graves. The remains of three German prisoners-of-war are placed in graves 25, 26 and 29 at the end of row 2. The German League for War Graves is aware of these three graves and have plans to exhume the remains. (9) Similarly to Hungarian POWs, German prisoners-of-war were also buried in the mass grave for Soviet soldiers. According to archive sources, 142 German soldiers were buried here; however, no record has remained on the time of their burial. Since the Soviet command did not publish any data whatsoever about these soldiers, only their numbers and the fact of their burial are known.

The graves of Romanian soldiers

The available sources provide scant information on the Romanian soldiers laid to rest in Debrecen’s Public Cemetery. All that is certain is that visitors (10) to the cemetery will encounter a mass grave in section IX containing 31 Romanian soldiers. However, the gravestone has no names on it and if one searches for data on those resting there, the cemetery records are of no help. If these soldiers in the mass grave died in the fighting for Debrecen, in all probability they were part of the “Tudor Vladimirescu” voluntary infantry division fighting in the Red Army and the soldiers of the 3rd mountain division. The uncertainty is increased by the fact that wounded soldiers were brought to Debrecen from other Romanian units too.

Apart from soldiers in the mass graves, three Romanian soldiers were also buried in sections XIX/2 and XIX/4, which no longer exist. It cannot be ruled out that when these sections were terminated, their remains were reburied in the mass grave. Another Romanian soldier, who was exhumed from No. 68 Poroszlay Street, was interned in section XV/3. Also lying here is Lieutenant Romulus Spolotek, but there is no additional data on him. Seven Romanian soldiers died in the Soviet military hospital, who were most certainly buried by the Soviets themselves among Soviet soldiers in section XVI/A. An additional source shows that four Romanian soldiers were buried in a grave for Soviet soldiers. However, for unknown reasons, these soldiers are identified as prisoners-of war. (This information is interesting because at this time the Romanian army was fighting with the Soviets as an ally, which would rule out the status of prisoner-of-war.)

THE MASS GRAVE FOR ROMANIAN HEROES IN DEBRECEN’S PUBLIC CEMETERY

The graves of Soviet soldiers

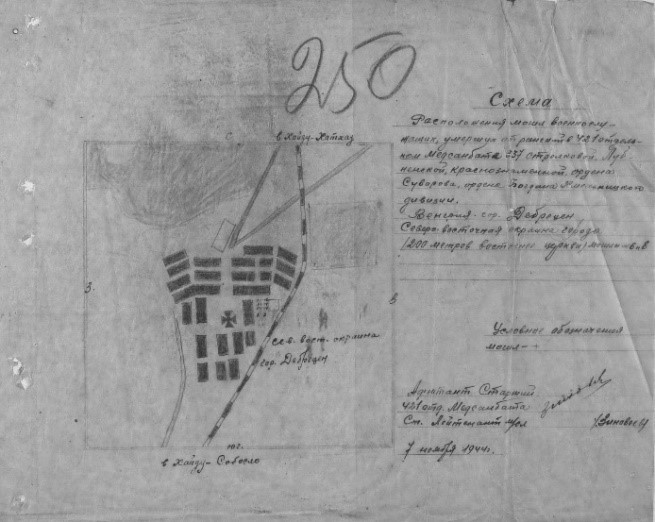

The Red Army suffered major losses of life in the fighting waged to occupy Debrecen. Until the recent past, no data that was anywhere near accurate was made public. During our research of the online database on Soviet losses, it surprised us that the Soviets had kept such a careful record of them. The results of our research also come from this database.

The table shows the losses of individuals from Soviet units that were directly involved in the fighting. Approximately a third of the data relates to deaths and two-thirds to wounded soldiers (estimated at around 900). No records were kept of soldiers from the Red Army who were captured, as in Soviet thinking this was a concept that did not even exist. (11) In the present case soldiers who went missing were included in the number of the fallen, since the records themselves on losses treated them as such.

A Debrecen elfoglalásáért harcoló szovjet magasabbegységek személyi vesztesége halottakban 1944. október 8. és október 21. között

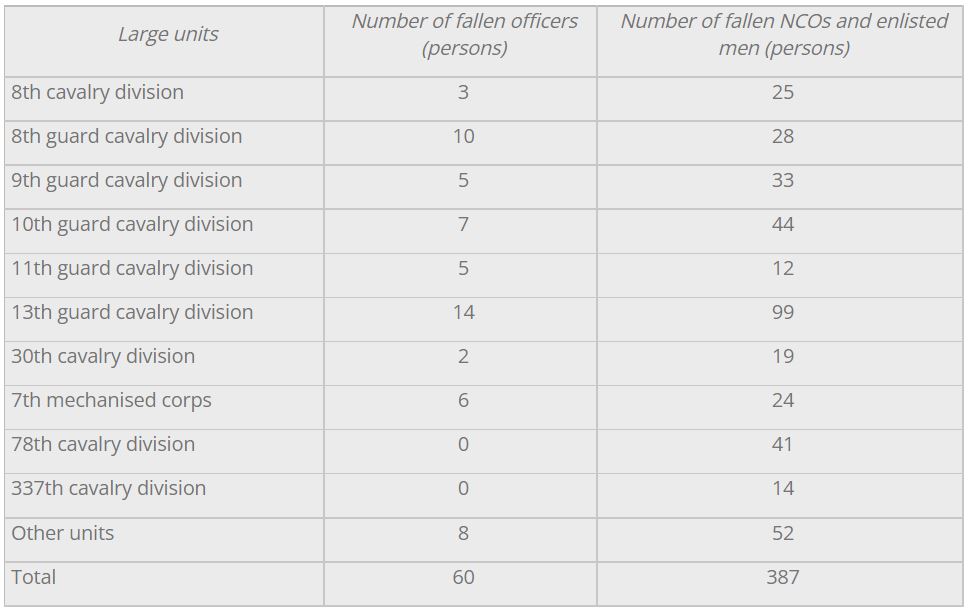

The fallen from the combat units were buried on the outskirts of the city or in the centre in military graves or small improvised cemeteries in various places. Since the fighting waged for Debrecen mostly took place in the western and southern parts of the town, a significant number of the scattered graves can be found in these areas. A great many graves for the 13th guard cavalry division, which suffered the greatest losses, were on the outskirts of the city. The commanders of the three Soviet tanks destroyed on 10 October 1944 (Captain Iovlev, Lieutenant Melkonov and Lieutenant Zaitsev) were buried in temporary military graves at the former road-mender house located at the crossroads of today’s main road no. 4 and Vedres-dűlő. Captain Iovlev was posthumously awarded the Hero of the Soviet Union Medal in 1945. Apart from them, a further eleven soldiers who served in the ranks of the Soviet army were buried in the same place.

A hadosztály 250. harckocsi ezredének három megsemmisített T-34-es harckocsija és hősi halált halt személyzetének sírhelye Debrecentől délnyugatra

Directly north of the location where main road no. 4 forks off at the Ebes, eight soldiers from

the 13th guard cavalry division were buried in two rows. From here towards Debrecen, there were

similar graves – two rows with four Soviet military graves each – where the dirt path opposite

the plastic factory meets the road. The site of the brick factory on Kishegyesi Road and on the

Jóna farmstead, located two kilometres west of Határ Road, were the final resting places for the

remains of a Soviet soldier each. Eight Soviet soldiers were buried by the brick factory on

Határ Road, and five Soviet soldiers in the Great Forest (Nagyerdő) by the pharmaceutical plant.

The grave of Sub-lieutenant Urlapkin, who was the section commander of the 1501st anti-tank gun

artillery division of the 23rd army tank corps, was on the site of the barracks on Péterfia

Street,

while the other three soldiers of the army corps were buried behind the Catholic church on Kassa

Road. Two of the five heroes of the same army corps were buried by the Lengyel barracks on the

edge

of Apafája forest along Sámsoni Road, and one each on Csapó Street, on the railway side of Kassa

Road and near the church on Attila Square.

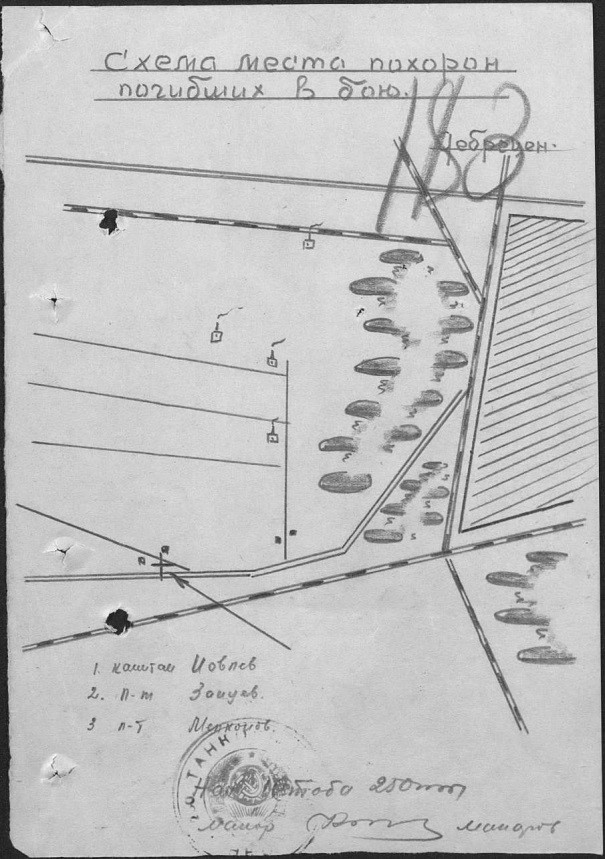

The 78th cavalry division had four small cemeteries on the fringes of Debrecen. The exact streets of the graves are difficult to identify based on the sketchy map attached to the list of losses but it is certain that the cemetery containing sixteen military graves was located north-west of the city, presumably along Böszörményi Road. The cemetery containing ten military graves can be found where Kassa and Sámsoni roads intersect. The third one, which consisted of fifteen individual graves and a joint grave for two soldiers, was in the centre of the city. The division’s fourth cemetery, containing eight in which nine Soviet soldiers were laid to rest, extended to the south-eastern part of Debrecen.

A hadosztály négy debreceni temetkezési helyéről készített térképvázlat

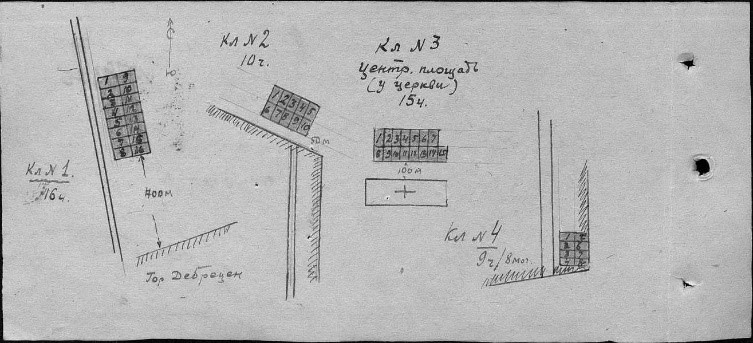

It was easy to identify the 337th rifle division’s only cemetery in Debrecen on the map we found; those who died at the dressing station of the 421st independent medical battalion were buried here. However, finding its present location proved to be far more difficult. According to the rough map, this place was somewhere in the north-eastern part of the city, 200 metres east of a church. The drawing clearly shows the graves as being to the west of the railway line to Nyíregyháza, i.e. towards the city, and the church in all likelihood is the Calvinist church on Árpád Square. Thus, the graves could presumably have been in the now closed Calvinist cemetery on Csapó Road. (13) Fourteen soldiers of the division were killed in the southern part of Debrecen during the fighting waged for the city; their military graves were located in Epreskert and along Mikepércsi Road.

A lövészhadosztály egészségügyi zászlóaljának temetője Debrecen délkeleti részén egy templomtól 1200 méterre, keletre

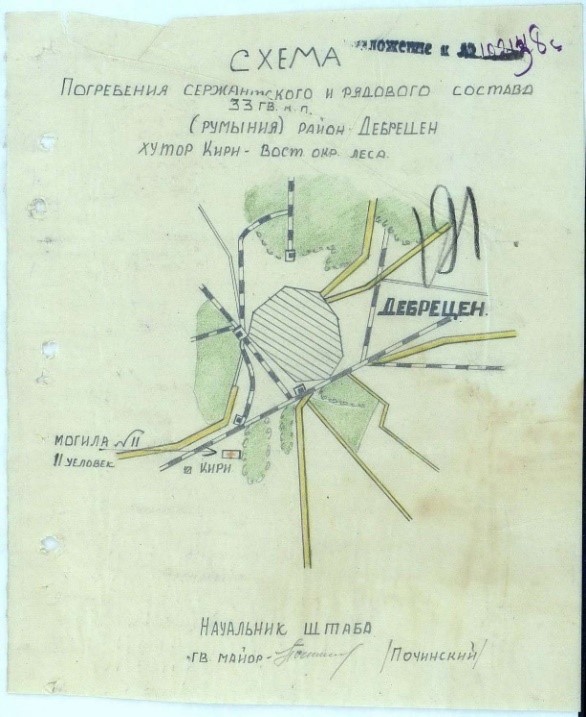

A 8. gárda lovashadosztály tevékenysége zömmel a Debrecentől délre eső térséget érintette. Több katonájuk a Hajdúszovát felé vezető út mellett lévő Jóna tanya területén, a Debrecentől 1,5 kilométerrel délre lévő Fekey tanyánál, és a Hosszúpályi felé vezető útelágazásnál volt eltemetve. Jelentős, 11 katonát rejtő tömegsírjuk volt a Vértessy téglagyár területén. Volt még egy további katonasírjuk a város északi oldalán is a Nagyerdő déli szegélyén, az Auguszta szanatóriumtól délre a Móricz Zsigmond körút mentén.

A 33. gárda lovasezred 11 elesett katonájának temetési helye Debrecen déli peremén

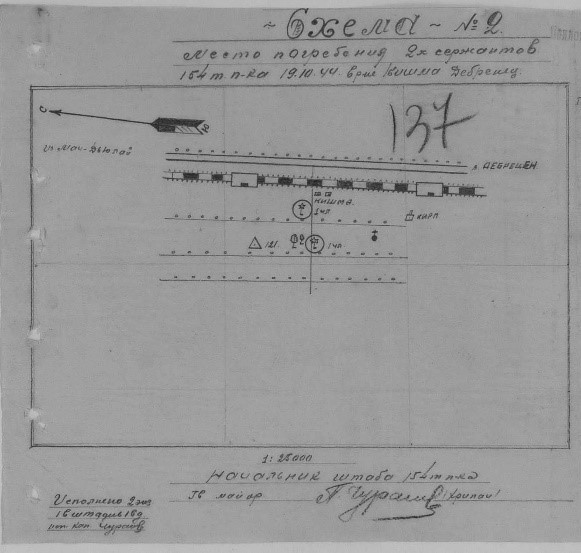

The 8th cavalry division joined the fighting west of Debrecen, at the axis of Balmazújvárosi Road. Of the cavalry’s 28 heroic dead the graves of Sergeant Bogdanov and Corporal Vasiliev were by the Lengyel farmstead, south of the wayside station at Kismacs, where their armoured vehicles were destroyed by the German and Hungarian troops defending their position. The 8th cavalry division buried two soldiers each at these locations: the Budaházi farmstead, lying south of the Látóképi Inn, as well as at the western edge of the city and in the city centre.

A hadosztály 154. harckocsiezrede Kismacs vasúti megállónál kilőtt harckocsijának személyzetéből meghalt két katona sírhelye

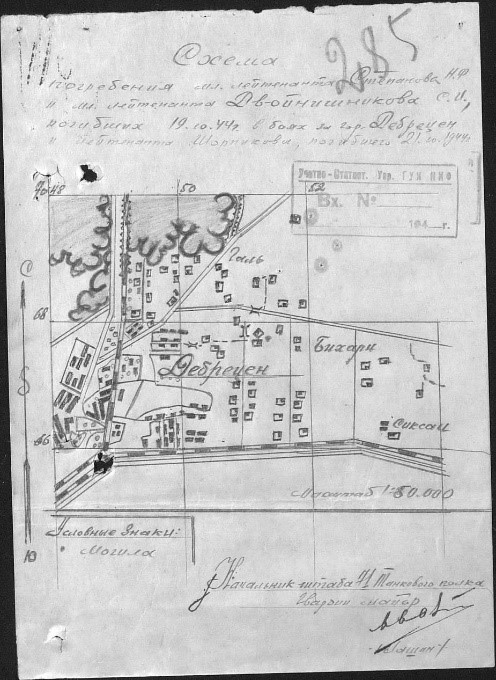

The Soviet forces setting out upon the final attack were assisted by the 11th guard cavalry division of the Gorshkov cavalry and armoured vehicle unit. This action was carried out by the division’s 39th guard cavalry regiment, which was supported by the armoured vehicles of the 71st tank regiment. The Soviet offensive, which reached the borders of Debrecen, was stalled when it came under fire by German tanks advancing from the south. According to the data we have so far, the cavalry regiment lost eight soldiers and the tank crews lost seven, including three officers. All three officers were buried in a grave several hundred metres east of today’s Veress Péter Street (approximately in the environs of today’s Pék and Szondi streets. Four soldiers who served in the ranks were also buried in this grave. The dead of the cavalry regiment were buried on the railway side of Kassa Road (14) close to the Sámsoni Road junction.

A hadosztály 71. harckocsi ezredéből megsemmisített három T-34 páncélos hősi halált halt személyzetének sírhelye a vázlatos térkép „Debrecen” felirata fölött

Eight Soviet prisoners-of-war were buried in what was formerly section XIX/3 of the Public Cemetery. These soldiers presumably died from illnesses in Debrecen between 7 and 24 August in 1944. The names of the deceased are recorded in the surviving section inventory book; however, a record of only some of them can be found in other databases. There is also a Soviet military grave in the Israelite cemetery on Monostorpályi Road. It is known from verbal communication that the soldier in question was murdered not too far away from the cemetery, which is why he was buried here, the closest cemetery to the place of his murder. However, in the database on losses his death is recorded as having taken place – like that of so many of his comrades – in the western area of Hajdúhadház, which casts doubt upon the data that can be read on his headstone.

The graves of American soldiers

American soldiers were also buried temporarily in Debrecen’s Public Cemetery. When an American bomber crashed on 2 June 1944, seven men out of the crew of eleven lost their lives. They were buried in grave 5 in row 6 of section XVIII. The section was later divided into several parts, thus the original site of the grave can only be approximately defined. The remains that could be found were exhumed on 10 April 1946 by the Grave Locator Division of the American Military Mission and temporarily buried in the American military (15) Two American heroic dead were later removed from here and reinterned in two different western European American collection cemeteries. The other five American aircraftsmen were transported to the United States by their relatives and given a final resting place in family graves.

The exhumation of soldiers and civilian dead buried outside cemeteries

The exhumation and proper reburial of the dead buried haphazardly in the city and its outlying areas as well as bodies that had barely been properly buried were on the agenda not long after life began to return to normal. The search for the graves of the heroic dead began as early as the middle of November 1944. Presumably thanks to the weather turning unfavourable, only 32 unknown Soviet soldiers had been removed from their temporary resting places by the end of that year. Unfortunately, only the data for these burials have survived and not where the remains were exhumed. Most of the work started in April 1945, when the spring weather provided suitable conditions for it. The project was coordinated by Debrecen’s medical officer service, thus there was an official body that systematically recorded the reports about those dead that needed to be exhumed and was able to outsource work to undertakers. During the work to rebury the dead in the Public Cemetery, which stretched over months, in fortunate cases it was possible to record in the inventory book where the remains had been exhumed from.

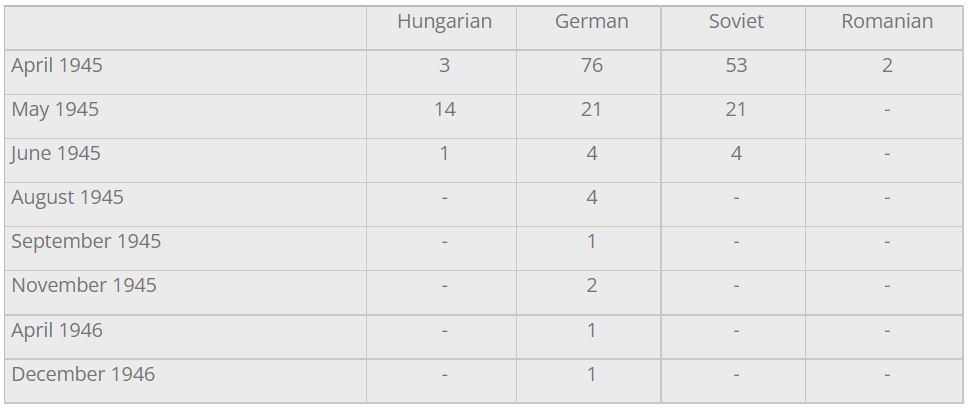

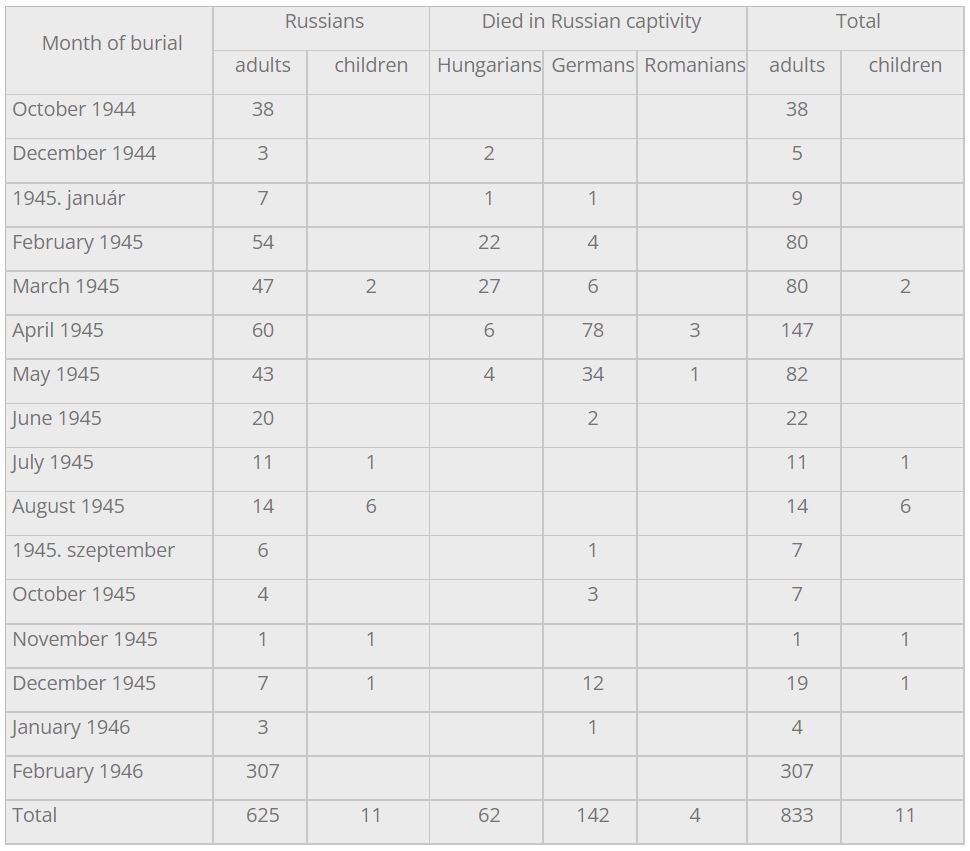

According to the records of the Public Cemetery’s inventory books, the following burials took place from the time of the first exhumations:

Közterületekről és a város határából 1945 áprilisától kihantolt katonák száma

The data of the Public Cemetery are supplemented by the records made in 1945 by Debrecen’s medical officer service, which contain some 190 entries. The list extends to unburied or hastily buried remains of military and civilian dead as well as to the buried carcasses and remains of animals. (16) The database is made especially valuable by the fact that it records the sites of the exhumation in every case. Since the site of exhumation cannot be found in the cemetery’s inventory books in every instance, these two sources can be well compared. Júlia Varga’s research report in which an additional 12 graves of Soviet soldiers are named, provides additional supplementary material. (17) Another table that deserves special attention is the one made by cemetery custodian Ferenc Kegyes: it principally contains Soviet soldiers and civilian individuals who were buried in the Public Cemetery’s sections XV/3 and XVI/A from the beginning of October 1944.

After the above, we would have reason to think that following the exhumations there would not be any more marked military graves left unidentified in the city or its environs. However, according to the cemetery’s inventory book, two Soviet military graves were discovered in 1950 next to the Greek Catholic church on Attila Square. Unfortunately, there was no data recorded on those laid to rest there. (18)

Kegyes Ferenc köztemetői gondnok jelentése a szovjet katonai táblába betemetett személyek számáról (19)

According to the research work carried out so far, the fighting waged for Debrecen claimed the lives of some 280 people from the city’s population. The primary source of our research was the data derived from the city of Debrecen’s death certificates, which we were able to supplement or clarify based on the data from the Public Cemetery’s inventory book. In 95 cases death was caused by a gunshot, a further 100 died under some kind of artillery fire or in air raids. Another 13 persons committed suicide in various ways. Belonging to this latter group were Jenő Nagybákay Sesztina and his wife Margit Csanak, who, not being able to bear the shock of the Soviet occupation, took their own lives on 21 October 1944. (20)

In examining the loss of life suffered by the city’s population, it can be seen that 19 October was clearly the day when most lives were lost: 54 died on that one day. On the following day, when the fighting shifted towards the north, the number of dead fell to 25. After this, the number of fatal casualties dropped continually although the looting and foraging by the Soviet troops caused civilian deaths every day because of violent encounters. Of course an exception to this was the German air raid of 27 October, which again increased the number of deaths.

THE MAIN ENTRANCE OF DEBRECEN’S PUBLIC CEMETERY

The condition of the graves today

The database attached to this volume contains the data for a total of 3,827 fatal casualties for soldiers and civilians taken together. (21) There are 778 Hungarian soldiers buried in Debrecen’s Public Cemetery; 242 of their graves have slant markers and 36 have inscribed tombstones, all of which can still be visited today. A further 91 labour service workers are in marked or unmarked graves in the Israelite cemetery on Monostorpályi Road. The other graves were either terminated or the remains exhumed and taken to Budaörs, while many others were taken home from Debrecen by relatives. The number of victims exhumed in the territory of Debrecen that cannot be linked to unknown Hungarian soldiers – thus entered in our register as resting in unknown places – comes to 49.

The number of dead soldiers and civilians who died in air raids on Debrecen and who are buried in the Public Cemetery comes to 898. The number of thus far identified civilian dead who died in the fighting in October or as a result of it is 401. The remains of 127 German and Hungarian soldiers who died in the bombings were reinterred in Budaörs. The number of dead in graves with slant markers is 406 and those in graves with tombstones comes to 297. At present, the graves of 300 victims that were terminated at any point after burial cannot be located. The remains of 81 individuals were taken home by relatives and there are 80 buried in unknown sites. Five dead bodies disappeared at the time of the air raids, while a further four soldiers were laid to rest in the Hungarian Military Cemetery (Honvéd cemetery).

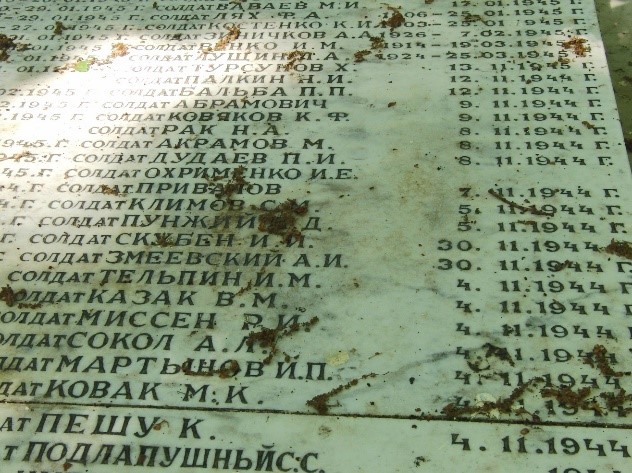

There are three remaining graves for German soldiers in Debrecen’s Public Cemetery. Some 200 Germans fell in the fighting waged for the city and a further 31 German soldiers were buried in section XV/3 as prisoners-of-war. A further 142 German prisoners-of-war were buried in the Soviet mass grave. Like in the case of the names of Hungarian soldiers, it is also true for the names derived from German databases that only a small number of them tally with the data on the remains removed in the exhumations. Of the Soviet and Romanian forces who occupied Debrecen there is a total of 1,358 Soviet and 33 Romanian soldiers buried in the city’s Public Cemetery. The names of 653 of the Soviet soldiers cannot be founds in either the records or on monuments.

Az első szovjet hősi emlékmű avatása a Köztemetőben

Az első szovjet hősi emlékmű avatása a Köztemetőben

A köztemetői szovjet sírkert hősi emlékműve és egy tömegsír feliratai

A köztemetői szovjet sírkert hősi emlékműve és egy tömegsír feliratai

In 1990, Júlia Varga, a Librarian Emeritus, carried out extensive archival research on Soviet monuments in Debrecen. Since then, the examination of the records on Soviet losses revealed some facts that could not be verified at the time. The back of the memorial to Soviet fliers, which stood on Petőfi Square until 1990, contained the names of five Soviet officers. However, it was later proved through research that none of them had lost their lives in Debrecen but rather at Szarvas, Mezőladány and Körösladány, and in any case all four of their names were also inscribed on the marble slabs of the monument erected before the Alföldi Palace (22) to Soviet officers.

A Petőfi téri szovjet (repülős) hősi emlékmű az első és a második felállítási helyen

A Petőfi téri szovjet (repülős) hősi emlékmű az első és a második felállítási helyen

The old monument to Soviet NCOs and soldiers was on Kossuth Street. According to the research so far, there were no soldiers buried under it, however, Soviet sources cite three Soviet soldiers laid to rest there, whom, however, cannot be found in the database of losses; these data are therefore awaiting verification. Pál Pátzay’s tank memorial, which was erected in the place of the first memorial and dismantled in spring 1990 (24) had nobody buried under it.

A Kossuth utcai első és a második szovjet hősi emlékmű

A Kossuth utcai első és a második szovjet hősi emlékmű

The history of the monument before the Alföldi Palace also has many strange details attached to it, since the plaques that were once there contained the names of 108 officers and one NCO, but 61 of these did not die in Debrecen, so in all probability they were not buried here and their names were mentioned here only with a commemorational purpose. The names of eight of the remaining 48 officers can also be read on the memorial on the mass grave in the Public Cemetery or on individual graves, which makes it likely that they are buried there.

The photograph showing Soviet soldiers offering an armed salute to the grave of a Soviet comrade before the town hall on Piac Street is well known by many people. The most recent research has proven that not just one but 22 Soviet officers were buried here. Debrecen’s medical officer gave a written order to the Gebauer undertakers on 7 April 1945 to exhume these remains and reinter them on the site of the first monument to Soviet heroes erected before the Alföldi Palace. (25)

MILITARY SALUTE GIVEN BY THE GRAVE OF 22 SOVIET OFFICERS BURIED IN THE PARK BEFORE THE TOWN HALL

The monument before the Alföldi Palace was disassembled in 1965 and the remains exhumed. The obelisk was re-erected in section XVI/A, in front of Soviet graves. In all probability, the exhumed dead bodies were laid to their final rest under the monument. The marble plaques were checked for the accuracy of the names inscribed on them and then stored in the Public Cemetery but not installed along with the obelisk. Pál Pátzay’s work titled A Debrecen Family was placed in front of the Alföldi Palace, and plaques made out of artificial stone containing 109 names were placed before it side by side. However, there were no Soviet soldiers buried under the monument at this point. This state of affairs lasted from 7 November 1967 to 23 October 1993, (26) when the monument was dismantled for good.

Az Alföldi palota előtti tömegsírra helyezett első szovjet emlékmű és koszorúzása

Az Alföldi palota előtti tömegsírra helyezett első szovjet emlékmű és koszorúzása

Katonai tisztelgés a városháza előtti parkban eltemetett 22 szovjet tiszt sírjánál

Katonai tisztelgés a városháza előtti parkban eltemetett 22 szovjet tiszt sírjánál

Regrettably, we have little relevant information on the Soviet soldiers reinterred in Debrecen’s Public Cemetery. No data has come to light regarding the exact reinterment places of a great many of the Soviet soldiers who had been previously temporarily buried in the closed-down cemeteries, nor about most of the heroic dead who had been buried in haste. According to some information, the remains exhumed from the closed-down cemeteries were reburied in section XIX and not by the side of their comrades; however, other sources do not verify this. (27)

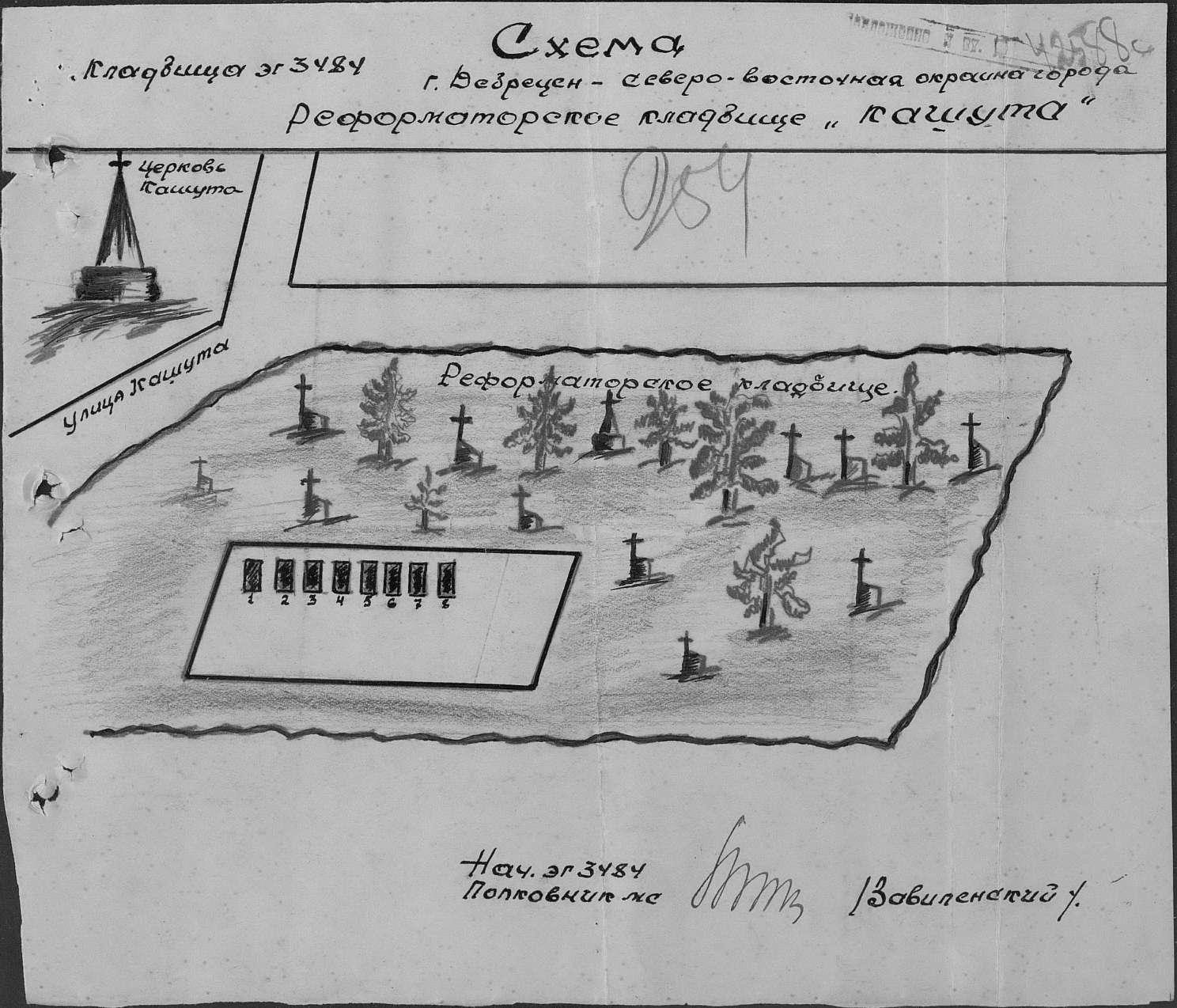

BURIAL SITE FOR SOVIET EVACUATION HOSPITAL NO. 3484 IN THE CEMETERY ON KOSSUTH STREET

BURIAL SITE FOR SOVIET EVACUATION HOSPITAL NO. 3484 IN THE CEMETERY ON KOSSUTH STREET

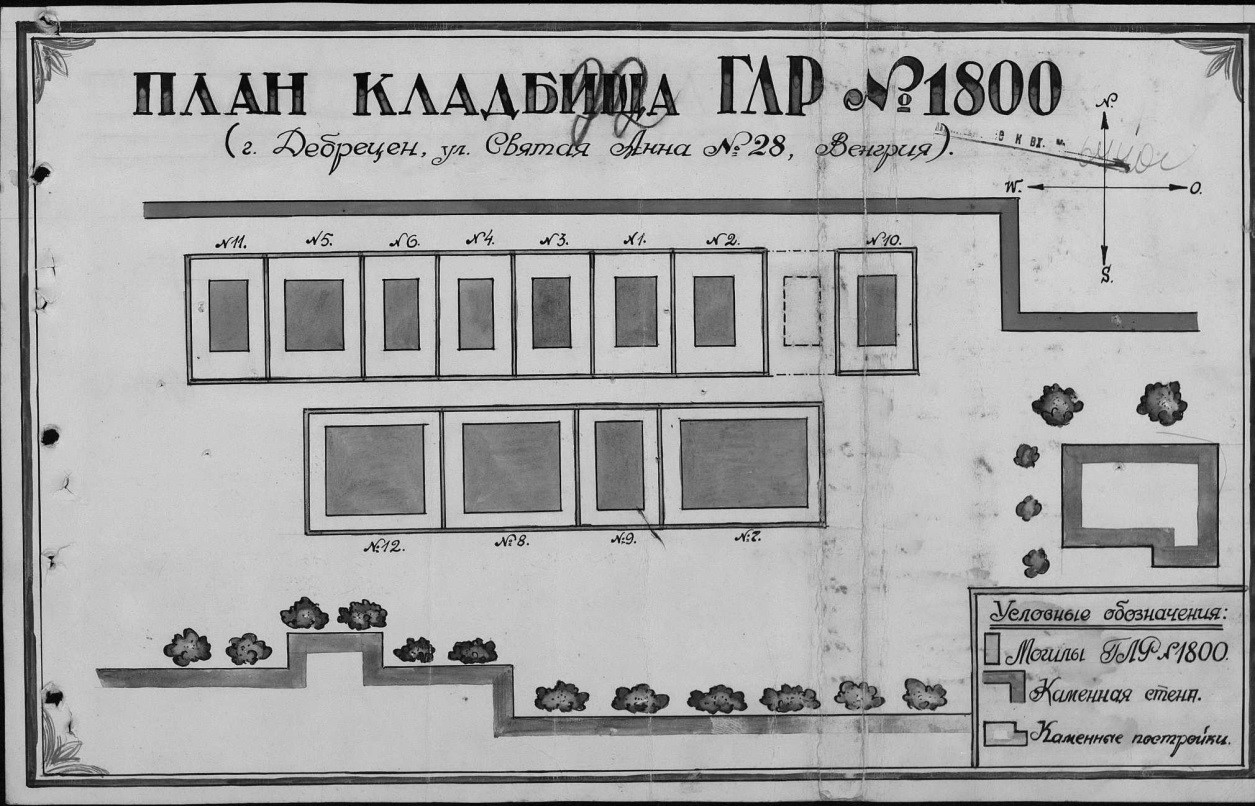

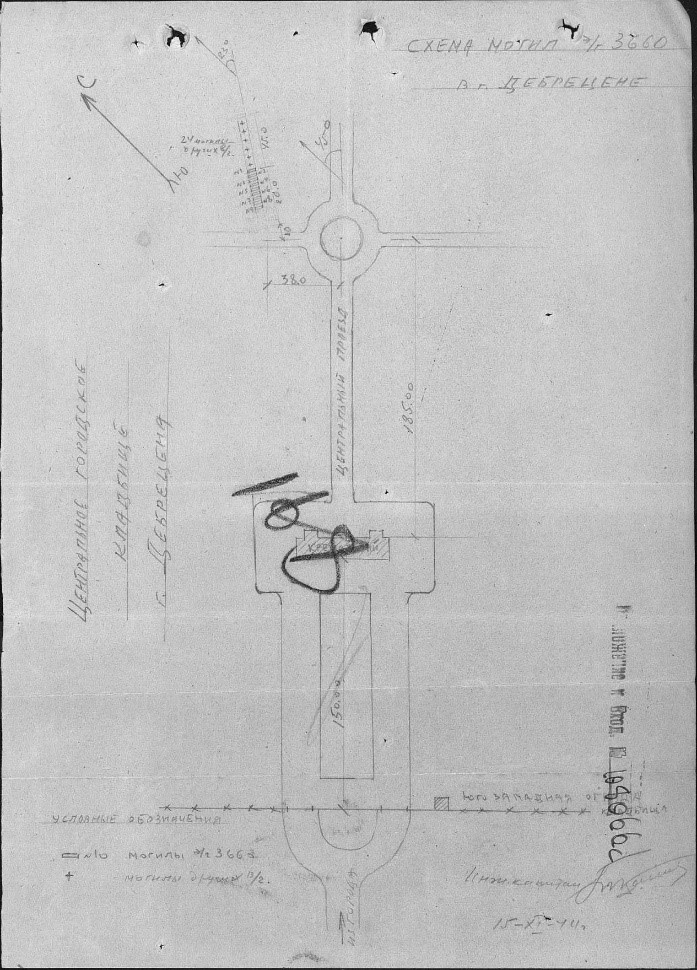

BURIAL SITE FOR EVACUATION HOSPITAL NO. 1442 IN THE SOVIET GRAVEYARD OF DEBRECEN’S PUBLIC CEMETERY

BURIAL SITE FOR EVACUATION HOSPITAL NO. 1442 IN THE SOVIET GRAVEYARD OF DEBRECEN’S PUBLIC CEMETERY

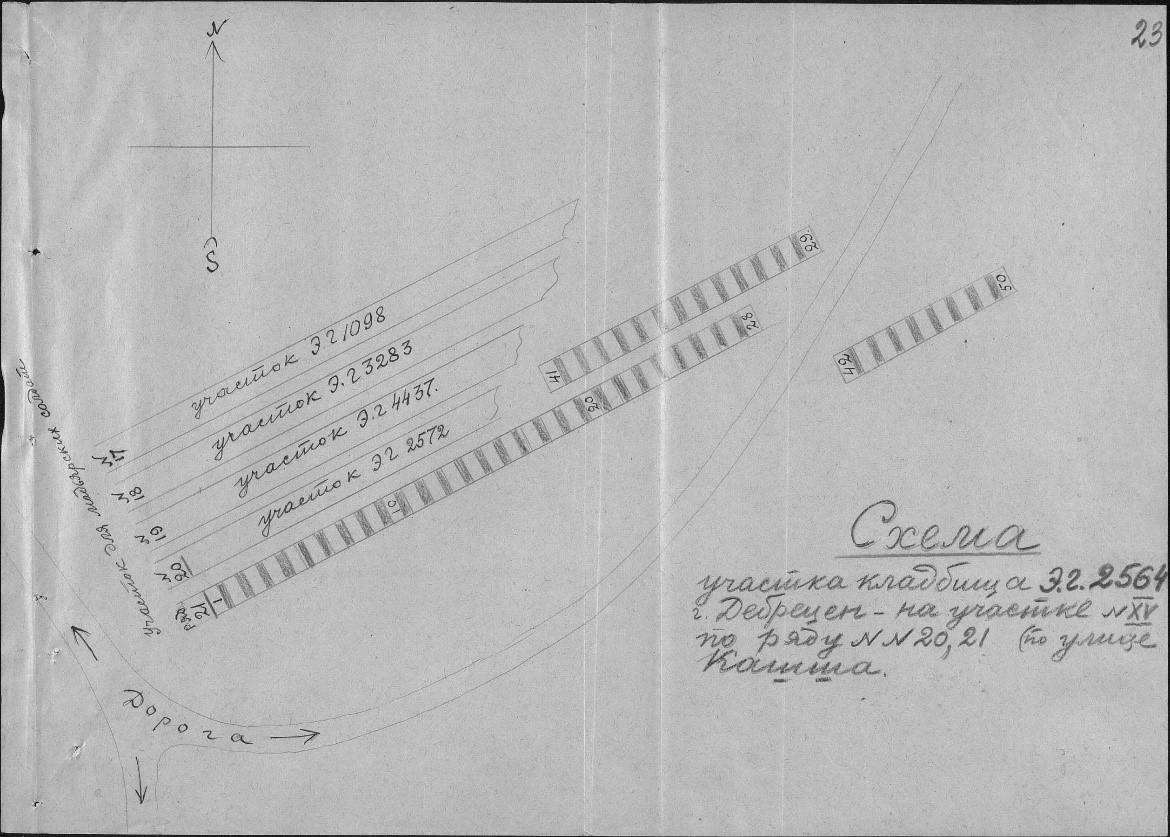

BURIAL SITE FOR EVACUATION HOSPITAL NO. 2564 IN THE SOVIET GRAVEYARD OF DEBRECEN’S PUBLIC CEMETERY

Postscript

The historical research work relating to military memorials in Debrecen, which has been carried out for two decades by dedicated individuals and the staff members of the Library of the Hungarian Army’s István Bocskai Artillery Brigade No. 5 (István Bocskai Library) and Debrecen’s Military Administration and Central Registration Command No. 2 are coordinated and consolidated with a professional background by the Őrváros–Debrecen’s Role in Hungary’s 20th-century History Public Foundation and the Debrecen Organisation of the Hungarian Home Defender (Honvéd) Army and Society Circle in the framework of “Forgotten Remembrance” War Commemoration Research Team. The summary data and historical facts on one of the most important military memorial sites, i.e. the military graves in Debrecen’s Public Cemetery, are published in Debreceni Köztemető – katonák [Debrecen’s Public Cemetery - soldiers] (edited by Sándor Csákvári, Dr Ilona Kovács and Attila Horváth, Debrecen 2016). Our text provides a sample of that publication to illustrate the knowledge we presently have at our disposal. Searching for new data and resources is on-going: our contributors continuously incorporate new information found in newly emerging documents and use them to reinterpret already existing data. Their enthusiasm and love of this subject are not borne merely out of the unquenchable curiosity of researchers: they are fully aware that tracing the data for military graves, tending to the graves, and identifying the Hungarian and international heroes and victims at rest in them while preserving their memory form one of the most important pledges in the peace between nations. Nurturing their memory and paying respect to the heroes of the past serve as a model for future generations as to how to pay worthy tribute to their predecessors.

JEGYZETEK

(1) The chapter is a partial and edited publication of the following work: Sándor CSÁKVÁRI‒Gábor FARKAS‒Róbert KISS‒ Katalin MARTINKOVITS: Betekintés a Debreceni Köztemetőben nyugvó más hadviseltek, háborús áldozatok kegyeleti körülményeibe [Insight into the mortuary circumstances of the other war veterans and war victims laid to rest in the Debrecen Public Cemetery] – In: Debreceni köztemető, katonák [Debrecen Public Cemetery, soldiers]. Debrecen, 2016. 111–162. (Papp József)

(2) The following chapters are an almost identical publication of the work: Attila Horváth: A második világháborúban mehalt katonák és polgári áldozatok sírjai a debreceni köztemetőben [The graves of soldiers and civilians who died in World War II in Debrecen’s Public Cemetery – In: Debrecnei köztemető, katonák. Debrecen, 2016. 53–92. (Papp József)

(3) These cards on losses can be accessed in the database at http://www.hadisir.hu.

(4) Presently we have no precise information available on the relocation of temporary graves of those buried on the premises of the university clinic.

(5) This is mentioned by Júlia Varga, who worked in this hospital at the time, in János Mata’s film titled Méltósággal [With Dignity].

(6) Júlia Varga: Második világháborús orosz katonák és gyermekeik sírjai Debrecenben [The Second World War graves of Russian soldiers and their children in Debrecen], research report (a copy is owned by the author)

(7) Hajdú-Bihari Napló [Hajdú-Bihar Daily], Vol. LIV, 24 November 1997.

(8) There is no Hungarian equivalent for the rank of Oberfähnrich used in the Luftwaffe. The two notes can be found under entries 2,860 and 2,859 in the Public Cemetery’s burial inventory book for 1944.

(9) Personal conversation with Mr Gábor Kohlrusz, a Hungarian representative of the German League for War Graves.

(10) A Romanian archives summary on Romanian heroes buried in Hungary. A copy is owned by the author.

(11) In Soviet thinking soldiers who had been taken prisoner had not carried out their duty to their country and were regarded as traitors. This meant that prisoners who were released and even their family members could be sent to Gulag prison camps.

(12) Az ideiglenes sírok kéziratos térképvázlatainak forrása: Центральный Aрхив Министерства Oбороны Российской Федерации (ЦAМO-РФ).

(13) The Calvinist cemetery on Csapó Street was situated on the northern side of Ótemető, on the site now occupied by the Technical Faculty of the University of Debrecen.

(14) Today called Kassai Road.

(15) Hajdú-Bihar County Archives of the Hungarian National Archives (MNL-HBML) IV.B. 1406/b 31551/1946.

(16) MNL-HBmL IV.B. 1408/a 209/1945

(17) Júlia Varga: Második világháborús orosz katonák és gyermekeik sírjai Debrecenben, research report (a copy is owned by the author).

(18) Varga Júlia: Második világháborús orosz katonák és gyermekeik sírjai Debrecenben – kutatási jelentés (másolata a szerző birtokában)

(19) MNL-HBmL IV.B 1406/b 298/1946

(20) Debreceni Képes Kalendárium [Illustrated Calendar of Debrecen] for 1946, Vols 45 and 46, p. 42.

(21) In: Debreceni Köztemető – katonák. Debrecen, 2016.

(22) The building, which still stands today, is on the corner of Piac and Csapó streets.

(23) Budapesten, a pesti Vigadó előtti téren állt az emlékmű pontos mása.

(24) https://www.kozterkep.hu/ ~ /7795/ Tankcsata_emlekmu_Debrecen_1970.html (utolsó letöltés 2015. november 30.)

(25) MNL-HBmL IV.B. 1408/a 209/1945

(26) https://www.kozterkep.hu/ ~ /2924/ Debreceni_csalad_Debrecen_1967.html (utolsó letöltés 2015. november 30.)

(27) Júlia Varga: Második világháborús orosz katonák és gyermekeik sírjai Debrecenben, research report (a copy is owned by the author).